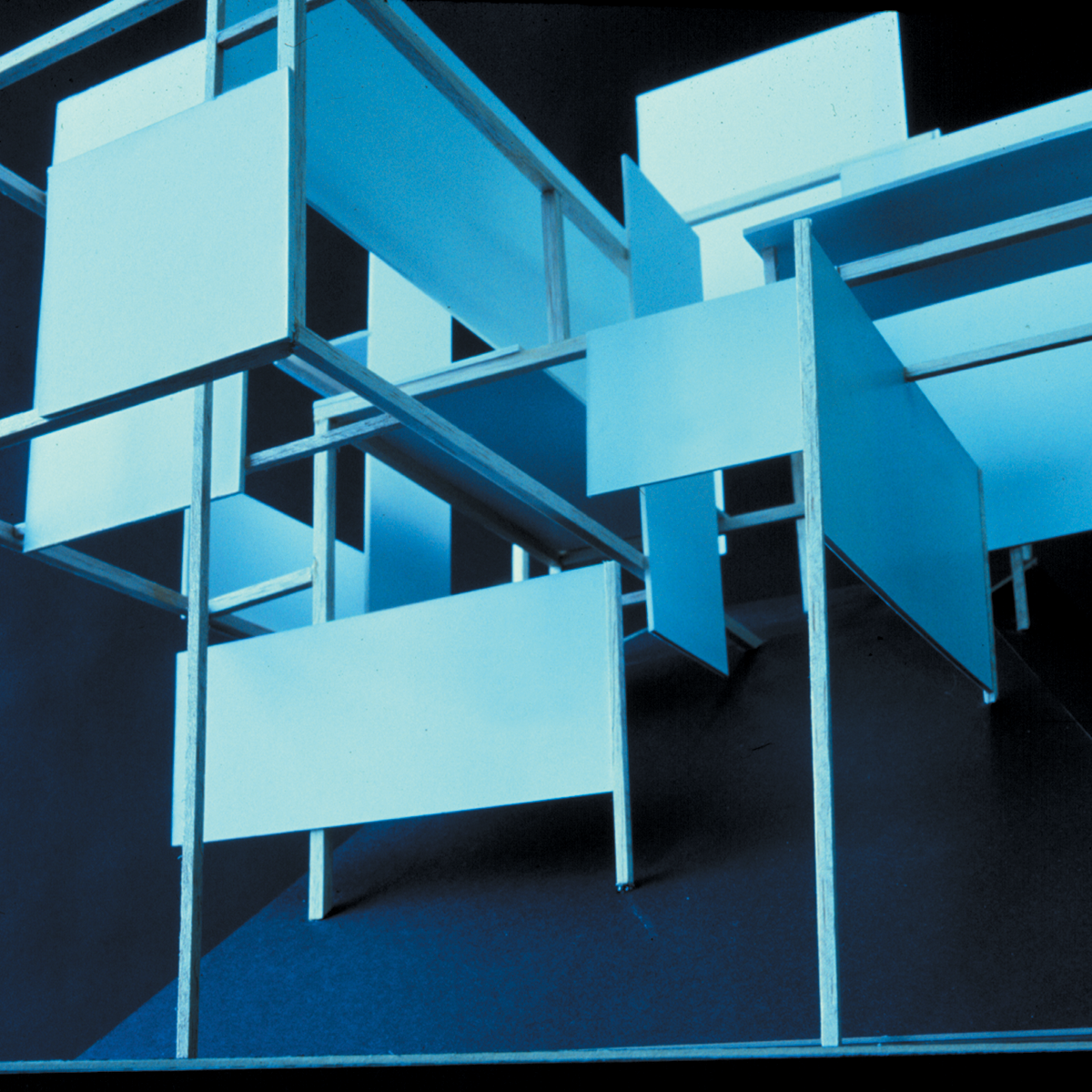

“The objective of this exercise is to choose a solid, cut it apart and reorganize the cut fragments in a new composition that is more beautiful than the original form from which it was derived.”

This is the first time in the Foundation curriculum that you are asked to create your own form. You can work with any of the following simple geometric solids: sphere, hemisphere, cylinder, cone, ovoid, ovoid plinth, round plinth, andrectilinear solids (of which there are many).

Design one or two geometric solids. Make four to six sketches in clay and choose the ones you like best. You will find that it is most straightforward to work with heavy, compact geometric shapes. Design forms that are interesting and beautiful in proportion. The forms should differ in size and character. If you choose to work with two solids, for example, a rectilinear solid and a cone of contrasting proportion, you may fragment both or fragment just one and use the other whole.

Divide the solid into at least three fragments. Use a clay knife to make straight cuts and 24-gauge copper wire to cut curves. It is not difficult to cut two interesting fragments, but it is difficult to get a third fragment that does not look like a ‘leftover.’ You must ask yourself, what does each cut do to the remaining part? The consequences of your actions become immediately apparent. Do not be too ingenious with your cuts, and do not feel compelled to destroy the geometric quality of the form.

If you decide to make that part smaller after cutting a fragment, you must return the clay to the piece from which it was cut, making that piece larger. In other words, if you take something, you must give it back. If a part is missing in the final composition, you will intuitively sense its absence.

Group the forms to create a beautiful composition. Use toothpicks or straight pins to hold your design together. You must use all of the fragments from the original solid, and they must add up—physically and visually—to a harmonious whole.

Establish dominant, subdominant, and subordinate relationships. Apply the same criteria to the fragment problem that you did to the simpler problems that deal with whole shapes. It is not a dominant/subdominant relationship if one shape overwhelms another. The fragments must complement each other. Every element should help the other elements look better. Make some proportion sketches to experiment with creating a sense of visual unity.

“In my experience, all designers have particular areas of sensitivity. However, sensitivities can be developed. Flounder around for a while. A dancer cannot say, ‘My back is not strong, so I will not use my back.’ The beauty of this course is that if you do all the exercises in order, you will find the weak points in your intuitive responses and strengthen them to become a better all-around designer.”

This exercise gives you experience working with positive forms and negative volume simultaneously. Be aware of the negative volume in your composition. Create tensional relationships between the positive forms and the positive and negative volumes.

Make a unified visual statement. You want to achieve a unified visual statement right from the beginning. The fragment problem can result in what looks like scraps piled together—or a design with real character. The solution’s success depends significantly on the grouping of forms.

Be careful not to take interesting forms and place them in an obvious arrangement with other forms (one/two, one/two, one/two). Moreover, be aware that if one part of your composition is very complex and another is very simple, the design will not unify. Your composition should look completely different from the original form but should be as balanced and even more beautiful.

Be aware of the movement of the axes. Think of that movement when you position each fragment. If you have all your fragments except one in dynamic positions, that lonely little static fragment will be difficult to unify with the whole.

You may want to use small sticks to make some axis sketches as experiments in creating structure and balance. Create an abstraction of as many lines or groups of lines as possible, making them go in and out of space. This will help you understand movement within a complex group of forms. If concavities are created, the lines of the concavity should move three-dimensionally. There is a tendency for students who have not worked three-dimensionally with lines to make them flat. (There is a catch here. It is helpful to analyze all the lines of the concavities created in the fragment problem using the method developed for the wire problem. However, I did not assign the wire problem before the fragment because I believed that the fragment should be more geometric in character. Otherwise, it becomes more sculptural and too complex for students to grasp, and much is lost.)

In General:

Spend 50% of your time designing an exciting and beautiful geometric solid and the rest of the time working with the fragments. If the proportions of the original are beautiful to start with, you have a better chance of getting beautiful fragments from it. You must love the proportions that you have made. If you work with two solids, take time and care to create forms that complement each other before fragmenting them. Keep all of your three-dimensional sketches. Do not destroy your early attempts as you create more successful compositions. You will find it very helpful to compare them.